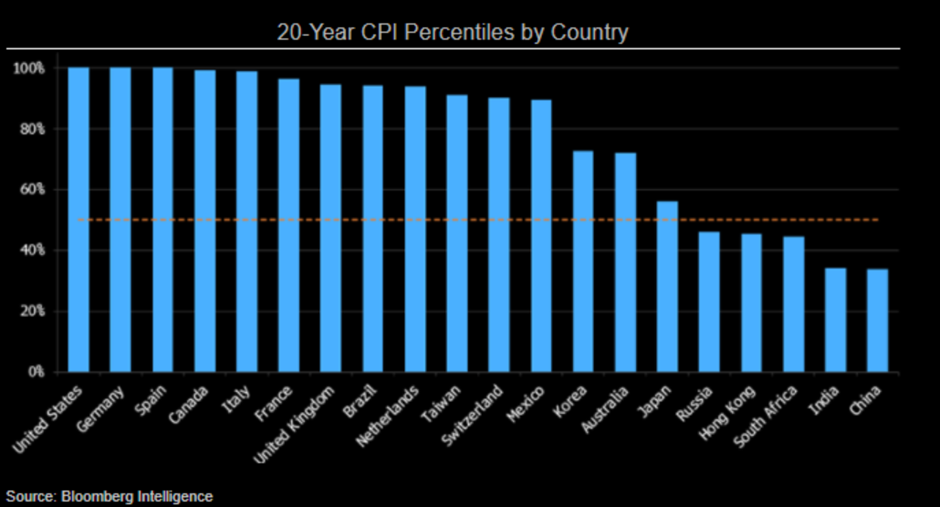

Despite (or possibly because) of a roaring global economy, the narrative seems to be fixated on the risk that runaway inflation will force the hands of central banks and trigger a global recession. In particular, the fear is that price increases will start a spiral of higher wages, feeding into higher prices, feeding in turn into higher wages … i.e., a repeat of the runaway inflation of the 70s/80s ending up in the dreaded stagflation (high inflation plus recession). Given where inflation levels are globally and relative to history (see Graph 1), the concerns are not totally misplaced. However, …

… no stagflation

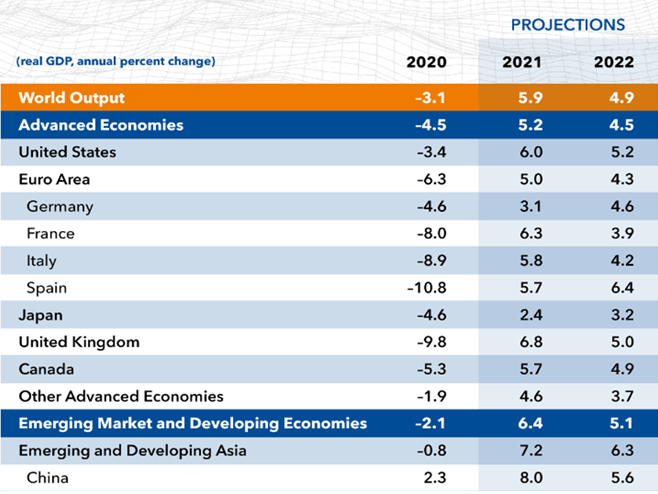

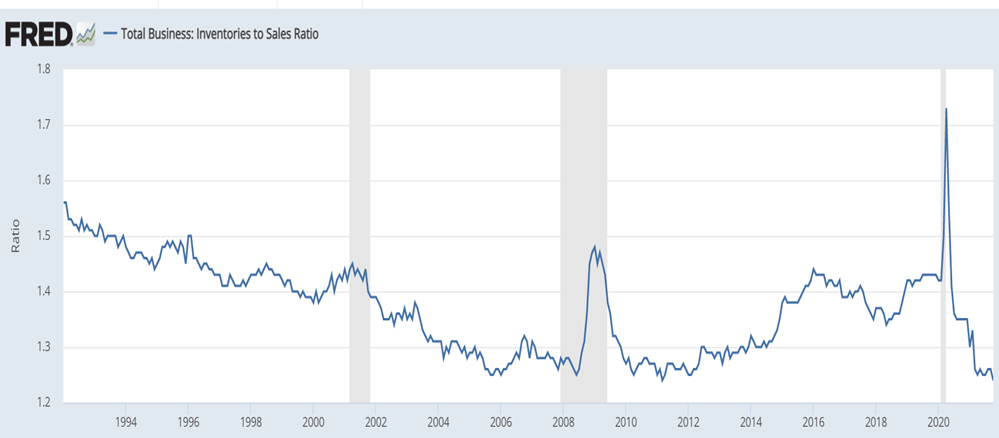

To be sure, the case and argument for stagflation is exaggerated, if not outright hysterical. To start with, most of the global economy is recovering well (very well) and is not about to keel over, even considering new Covid variants (See Graph 2 – IMF GDP Projections). Irrespective, the key point is that stagflation, conceptually and practically, needs a permanent supply shock, e.g., a fourfold increase in the price of oil (from US$3 to US$12 in the 70s). To be sure, the current supply shock (attributed to Covid) is undeniably sizeable (see Graph 3), further exacerbated by pent-up demand roaring back amidst low inventories and logistics bottlenecks. Indeed, while the impact was undeniably significant, it may also be temporary as “normal” production comes back online. One possible lasting effect may be a rethink of the well-established “just-in-time” inventory approach, triggering an incentive to build bigger (as in more secure) inventories … albeit in some sectors, at the margin, and with no considerable and permanent impact on prices.

… bad inflation, good inflation

The issue then becomes will inflation spiral out of hand globally, disrupt economic activity and lead to highly restrictive monetary policies, tight financial conditions, and ultimately market decline, i.e., bad inflation? And here the 70s and 80s are the most recent (only?) historical precedent to go to for analysis and comparison. Or will price increases result in lowering demand further and “gently” managed (the “ahead of the curve” analogy!) by active monetary policies, thus quickly stabilizing the system amidst modest impact on growth, i.e., good inflation? The difference will be determined in large part by the amount of “passthrough”, or the extent that increases in prices/costs will become ingrained in the economy.

… passthrough

The rule of thumb is that the cost structure for the aggregate economy is roughly attributable 60 percent to labor, 30 percent to commodities, and the remaining 10 percent to “others”. As it were, the sharp price increases in commodities prices (food and energy) have indeed generated substantial concerns and inflation scare at the retail (headline) level. However, food and energy are notoriously considered volatile by policy makers and indeed susceptible to be reversed, quickly. Hence, the focus on “core” inflation by policy makers and their view of a ‘transitory” nature of the headline price pressure, i.e., no permanent passthrough. The notable exception is for low-income countries (EM) where food and energy have a much larger weight in the CPI basket and long-lasting effect (remember the Arab Spring?!)

… the labor market puzzles

According to the US Bureau of Labor Statistics, in the US alone employment is 5 million units lower compared to pre-Covid. These statistics alone would sap any alarm of a wage-price spiral … were it not for the offsetting statistics that labor participation declined markedly during the pandemic by approximately a similar amount and going back to a level not seen since the 70s, i.e., something seems to be changing in the (global?) labor market. Indeed, the decline in participation may be permanent courtesy of the pandemic (e.g., health risk, schools’ closures, less availability for childcare, telecommuting, early retirement, etc.). Furthermore, and crucially, the widespread expectation is for wages in major markets to go up, this almost independently from inflation. Indeed, it is a well-known fact that wages (particularly in the USA) have markedly lagged productivity gains and, therefore, corporate profit gains. Hence, tight labor conditions, structural gains in historically depressed wages, coupled with sharp increases in prices (food, energy, shelter) surely could turn out to be the necessary fuel for inflation to overshoot as in the 70s/80s, thus forcing the hands of the central banker, right?

… not so fast

While the arguments and facts above seem reasonable and undeniable, there are plenty of equally compelling reasons tempering the fears of a global wages-price spiral and runaway inflation. To start with, the labor comparison with the 70s is totally misdirected. Albeit with some regional differences, the labor market is now a global market. Since roughly the beginning of the new millennium, two billion workers joined the global labor force, thus keeping wages in check. In addition, technology (robotic) has been labor-destructive (now it takes a lot less labor to build a car). Furthermore, and with the possible exception of Europe, labor unions seem to have lost a lot of their bargaining power, at least on the wage front. Add to that larger frictional unemployment (the reverse of low labor participation) and there seems to be plenty of reasons to appease concerns of a wage-price spiral as in the 70s/80s.

… the profit margin squeeze

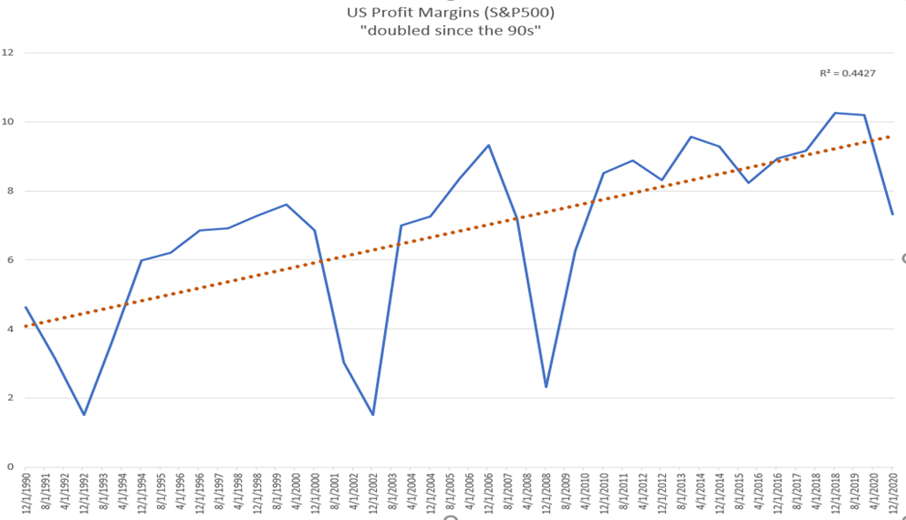

While some “recouping” of wages versus corporate profits is a definite possibility, it may not be a sufficient reason for prices to go much higher. Indeed, costs push inflation will ultimately depend on the capability of corporations to charge higher prices to the consumer, running the risk however that the “passing through” could destroy demand. To that end, and albeit with notable regional and sector differences, the (very) healthy level of profit margins in some of the major markets (Graph 4) would argue in favor of the capability of corporations to absorb at least part of the costs. And here is where the impact of higher costs could exert a toll on valuation and the market. To the extent that the latest markets rallies have been sustained by healthy margins and growing EPS, cost increases and tighter margins could have a sizeable impact on the market. Nonetheless, and to the extent that the resulting market volatility would renew concerns on valuation, generating healthy corrections, the result could still be “good inflation”, providing good investment opportunities.

… global differences

To be sure, there are noticeable regional differences. Most prominently, Emerging Markets (EM) in general are very poorly positioned to face a bout of global inflation, even if good inflation. To start with, higher global rates and yields create pressure on EM FX, with sizeable passthrough to local prices. In addition, for an equal amount of inflation, their policy responses need to be all the more forceful to be persuasive. Latin America is the case in point where the need to temper inflation has already resulted in very hawkish monetary policies across the region, triggering expectations of imminent recession, credit pressures, FX weakness, etc. The EM exception is Asia where inflation seems to be in check … and where China has plenty of tools available and willingness to use them!

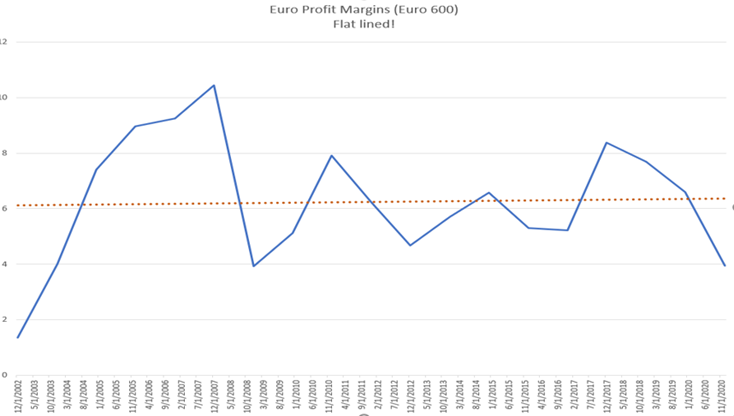

Europe is starting to generate concern as it may be falling “behind the curve”, with the monetary authorities reluctant to outright pivot to a hawkish stance despite historically high price pressure in major eurozone economies (see Graph 1 above). Indeed, the scope for policy errors (leading to bad inflation) seems to be sizeable there. Labor unions are still powerful, while profit margins have not benefitted as much as their US brethren (see Graph 5 below). Add to it the much higher dependence on energy and potential higher pressure on price levels could require harsher policy measures down the road and derail the recovery … with obvious massive market risks!

… conclusions

- Despite the undeniable and substantial jolt to the global price level, there are good reasons to expect that inflation will remain benign, i.e., it will not trigger the need for very harsh, coordinated global policy responses as we saw in the early 80s … i.e., no market crash.

- Indeed, to the extent that the recent price increase will force the monetary authorities to pivot away from exceptionally accommodative measures (QE, ZIRP, etc.) and result in higher real rates (the best evidence of good inflation), the overall effect may be very similar to a typical late-cycle policy tightening with a healthy market correction.

- However, and to the extent that high costs will be offset by lower profit margins, the impact on valuations and the financial assets may be more pronounced relative to typical cycles.

- The exceptions to this relatively benign outlook on inflation are clearly EM, where the risks are at the highest relative to the last few decades, and Europe where the authorities seem to be reluctant to pivot in favor of engineering “good inflation”.

… strategy

- Tapering of QEs, end-of-cycle monetary stances, volatility, and a potential squeeze on profit margins all argue for a Defensive (i.e., non-cyclical!) portfolio strategy with a Value and Quality factor tilt for the core position.

- Despite the widespread concern on aggregate valuations, there are plenty of opportunistic stories, or Satellite (e.g., high margins, low leverage, and structural and unusually strong growth) to build a Barbell portfolio, i.e., defensive Core, aggressive Satellite.

- Equity remains the asset class of choice … recommending fixed income other than cash (or no duration) is borderline with criminal. There are plenty of good dividend opportunities to satisfy the need for (better!) income.

- Regionally, Asia (EM & DM) appears to be better positioned to weather the current bout of inflation. Europe remains a (cautious!) value story only, at least until the authorities pivot persuasively to a more hawkish stance to keep inflation in check. EM offer little attraction and remain the global region most vulnerable to inflation trends. Some US sectors and industries remain the place to find very attractive opportunities benefiting from very wide profit margins, low leverage, and structural growth.

Simon Nocera (snocera@lumenadvisors.com), Lumen Global Investments LLC, December 2021